When words of conversations are many years lived.

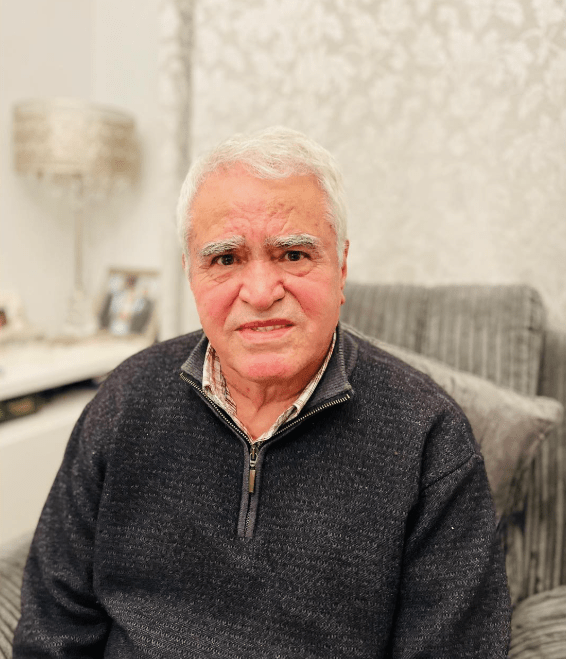

Arrived at London in October 1971 with two other friends, the 24-year-old Mehmet Amca was keen to find the factory he was assigned to work at. He laughs as he tells me he headed straight to the factory from the airport. Disappointed but not surprised that the factory was not open on the late Saturday evening. The three friends visited their place of work first thing the following morning. Only this time they faced the dilemma of all the roads and houses looking the same, they got lost amongst Sunday morning church goers and found themselves at Dalston police station asking for directions.

Once again, the factory was closed and this time they were taken to an all men’s working café in Newington Green. ‘I wasn’t aware at the time, but I would spend most of my weekends in these cafes.’

Not allowing time to kill their enthusiasm, they arrived at Tudor Grove in Hackney,

‘I still remember the address, like it was today.’

This time determined not to be put off by time or day, he started his shift at 8am. Before break, he looked around and noticed everyone’s head in synchrony with the revving of their machines, dipping and diving, up and down. This was the moment of realisation, what felt like a terrible mistake he had done.

‘I had my own shop with 6-7 members of staff working for me, I was comfortable. I had no interest of leaving my business, home or heavily pregnant wife. It was my mother who wanted me to experience Europe. When an invitation was sent out for labourers and a work permit prepared in less than two months. It was fate my feet followed.’

When he received his first brown envelope on Friday and saw £13 instead of the agreed £40 it was already turning point for him.

A community was built visiting café’s every weekend trying to find the factory that offered the best deal. Within a year Mehmet Amca decide it was him who would offer the best deal and opened his own factory.

‘Your family back home must have been impressed,’ I ask.

‘I couldn’t really show off about it, although we had our own factory, we weren’t making any money, so we had to close it down.’

After living in shared accommodation for a few years they decided it was time to move on. Private landlords were not willing to share advice on how to do this for obvious reasons. So, Mehmet Amca opted for the less conventional way of house hunting and his friend with a black belt stepped up to help squat into what would become their family home for several years.

During this time, he become the manager at an established factory introducing a system both the employer and the employee would be happy with. Within weeks the factory had almost doubled the number of garments they were producing. People were approaching him at the grocery store, cafés, pubs, family gatherings, all asking for a job. He helped many as he could; he reached out to relatives back home in his village to come over and start up their own life.

‘The factory was booming, everyone was happy, we were all making a good income. I had my heart set on a white sports car, so I brought it. The only trouble was I had no licence; it wasn’t only the licence that was the problem; I had no idea how to drive. I had asked the salesman to drive the car to my address. I’d sit in the driver’s seat play around with a few of the switches then get out. Once I felt ready enough to turn the ignition my feet didn’t want to cooperate with my mind and drove headfirst into a brick wall.’

During what were known as the heydays there were some turbulent times. Not every day was plain sailing, far from it. There were many difficult times too, and it was during these times, friends became family.

Of course, this was all in return to a community built in the trio of cafes, pubs and factories.

‘Sometimes I get stopped on the street, by someone who reminds me I helped when they first came over or when they needed a job.’

He points at his wife,

‘But it’s your Yenge that was my biggest motivation and supporter. I’m an ambitious man, I like to dream, but if it wasn’t for her tenaciousness, none of those dreams would have come true.’

I admire SultanTeyze’s confidents as she draws back her shoulders to acknowledge how true those words are.

Love to hear your view