Erol Amca had a factory in the East end of London that staffed over 40 workers, which now occupies as a trendy pop-up studio. This is the factory I spent several school holidays racing in fabric carts, and started my first ever job as a button packer. Might I add, those spare buttons you find in your blazers and coats require serious skill from an 8-year-old. Like most factories it was made up of several equipment to facilitate each step of the manufacturing process. The cutters table and steam press were dominated with moustached men flexing their muscles. The buttonhole machines, overlockers and finishers were neatly arranged more for the female workers. Centralised was the wooden manager’s table, where he ensured the pieces of fabric once cut and under pressed were divided fairly (at least in his eyes) to the machinist, before returned to the top press. But, it was the colourful characters behind the rows of grey machinery that were decorated with dried flowers and pictures of loved ones that fascinated me. This was not a clothing factory, but an institution of journeys travelled, communities built, and stories told.

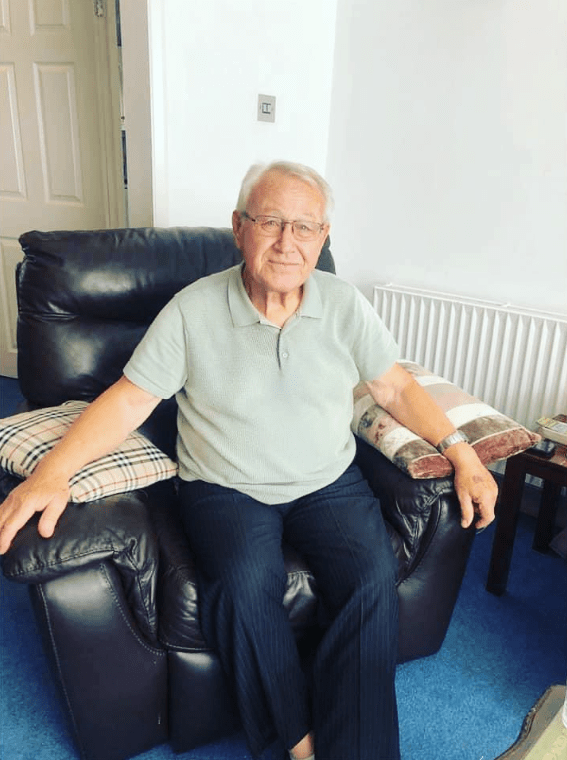

2025 marks 50 years since Erol Amca left Istanbul and moved to London, although the intention was to work for four years then move back …

With the economic crises putting pressure on small businesses in Turkiye Erol Amca couldn’t ignore the advert inviting tailors to work at clothing factories in the UK. At the time he was the owner of a small shop making custom leather goods, like many businesses he complained most of the supplies were on credit. He applied for a British work permit, not expecting both permit and passport to arrive in a matter of two weeks. Where everything was progressing so quickly, he was feeling unsettled and replied with a panicked response that he was not ready to fly out due to incomplete orders. This, of course, was not true, he needed time to come to terms with this big decision he was contemplating. 6 months later the firm got in touch with him again, he was told by his wife, Mine, that his passport was missing. With much convincing from friends and family, Mine Teyze miraculously found Erol Amca’s passport under the rug.

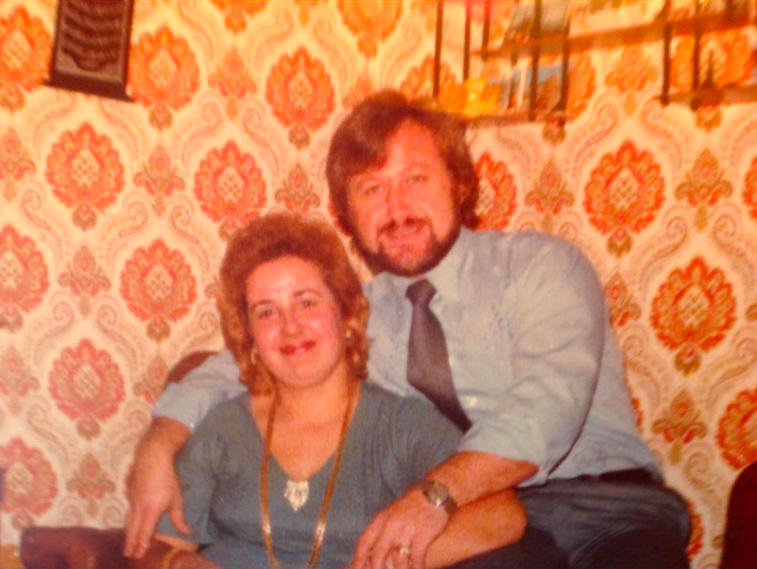

‘I left in tears. I was leaving behind my wife and two children, one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. I reminded myself it was temporary and for a better future. I told Mine I’d write to her, and I did, twice a week. There were times when I couldn’t find paper to write on, so I wrote on brown paper bags. I wrote about everything, from the shades of the grey skies to the greenery in the parks, but most of all I wrote how much I’d missed them all.’

Two months later Erol Amca was united with his loving family. Like most expats of those times, they too lived in shared accommodation. The living conditions were bad. So bad that they moved five times within two months.

‘One family we lived with used the bathtub to wash their dishes, each time we wanted to have a bath there was a film of fat around the tub. We decided shared accommodation wasn’t for us and although above our budget we wanted to move into our own place. Only landlords didn’t want children. They were willing to rent their property to us if we had a dog, but no children.’

The 4 years they had set out for themselves had well and truly passed, the children had grown, and they were no longer living in shared accommodation. After working in several different factories Erol Amca decided to open his own factory in 1984 to which his son, would take over in the mid-90s and continue to run until the early 2000s.

‘By the time I opened the factory with my business partner I was a different person to who I was when I first arrived. My father and brothers were all part of the military, as for me I was very reserved, conservative even, that changed once I moved to London. This country helped me grow as a person. My business partner was robbed at gunpoint on the way back from the bank with all the wages, and whilst we were panicking about how to tell the workers, they stepped up to support us. That’s how it was, we looked out for each other, we tried to create opportunities for people that didn’t have the right paperwork, who then went off to do bigger and better things. More importantly friends became family, like Nezih and your father.’

At this point of the interview, we both well up, my eyes with tears, his with kindness.

One of the conversations I remember from my childhood is how common it was for people to hop from one factory to another in a matter of months or even weeks, but people would work at Erol Amca’s factory for years and be satisfied.

The factory wasn’t only the home for manufacturing. It was a hub for embracing each other during the birth of one’s child, bringing over a loved one, gaining the right to remain, becoming a British citizen, graduations, weddings and more. The bond only grew bigger when reaching out in grievance. If someone was off sick, they would take turns to cook for them and send over food and endless remedies.

It was in factories like this where not only jackets were sewn but it was the seeds sown to build a community where the fruits ripen in society today.